M.G. Mauro, considering how your work has evolved over a long period, I’m struck by a double orientation: from intimate and private spaces toward the expanse of vast damaged landscapes, and then toward a more lyric nature, no longer devastated by humans. How do you explain it?

M.B. The answer is tied to my personal experience. Since I was a child, I have wondered about my “place” in the world.

Without a doubt, my artistic calling comes from my search for an answer to this very simple and universal question. While I was studying,

I understood that art cannot just be an egocentric therapy, other people must also be able share what the artist expresses.

But when I was looking for a subject to spark this exchange and special connection with views, I didn’t come up with anything

more interesting than expressing uneasiness, that is the difficulty I have in finding a reason for existing, my place in society.

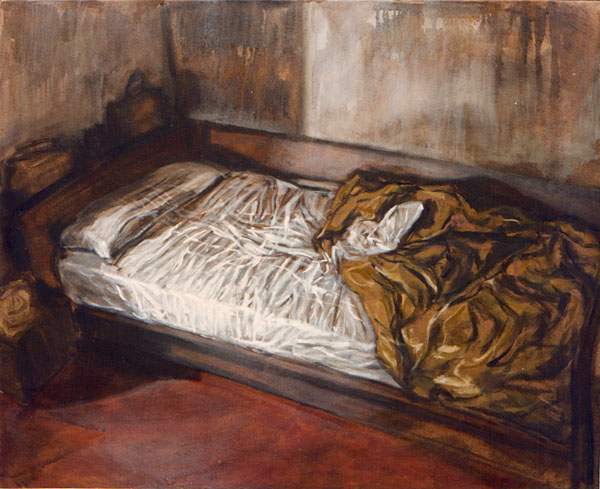

Now, this is expressed in the relationship between interior/intimacy and exterior/unknown in my bedrooms. As far as landscapes destroyed

by war or other forms of human intervention are concerned, the question is always the same, yet projected on a broader social scale:

what is our place in the world and what type of relationship do we have with it? Concerning the more lyric work on landscapes,

I see an attempt to reconcile with nature; in the end we are products of nature and probably, if we used our brains more, we would

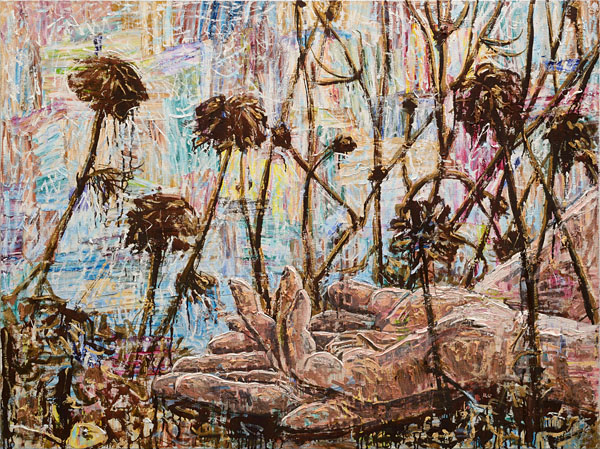

find a respectful balance with it, rather than domination and brutal exploitation. That said, the species depicted in my paintings

are often mutant species that don’t really exist.

I paint suspended time, the question without an answer, the probability that we still have a long way to go before we find our place.

Perhaps I should admit that I am a believer, but without a god.

M.G. Could we therefore associate your path with a tradition that, from Romanticism up to the great American abstractionists like Rothko, passes through numerous painting styles, which suggest that it is fundamental, for both the artist and viewers, to look for a sense beyond what the naked eye can see, above all in a secularized world like ours?

M.B. Yes, I feel that is precisely my artistic course. I find post-war abstract painting fascinating, but above all that which comes

from reality. In my opinion, reality, through its depiction, is far too important to relinquish. All of it belongs to the language of

drawing, painting. An artist who undertakes telling stories starting from this type of materials has enormous possibilities ahead and

can access different areas of awareness.

Personally, I believe I capture the restlessness and troubles of our age, our space/time: I try to make them visible using a poetic

approach, “lyric” as you rightly said. So subjects emerge, who speak about solitude, the difficulty of facing others,

nature, themselves, and a relationship with chaos, entropy, remains.

I love paintings that question us.

M.G. Without being excessively tied to the past or anti-modernist, you show an attachment to representation that seems nourished by a fecund and essential relationship, for you, with the history of Italian painting from the Renaissance onwards. We have already talked about this, but could you tell me again, more precisely, what role legacy has played in your training or growth and the tie you have with it today?

M.B. I don’t want to sound pretentious, but growing up in Padua and studying at the Academy of Fine Arts in Venice,

I was surrounded by a lot of magnificent works of art! In Padua, for example, the frescos by Giotto, Giusto De Menabuoi,

Altichiero da Zevio, Jacopo Avanzi. In the Gothic chapels and before the works by the Italian primitives, you really experience

the total work, you’re enveloped by, immersed in the painting, in the story and the images. Plus, I have to emphasize that

the paintings and sculptures are perfectly integrated into the architecture, since they were conceived in the same material:

stone, lime, oxides. Therefore, in the same mineral environment, an environment that is extraordinarily homogeneous.

I then rediscovered this sensation of painting that wraps around the observer in Tintoretto, in Titian and in the Mannerist

artists in general. In my opinion, these works don’t fit in as well with the architecture because they seem cut out,

separated by heavy wood frames. In other words, we’re a long way from the lightness of the previous periods. Despite this,

I love the Mannerists: they elaborated theatrical works, which invite us to take part in a performance. With Tintoretto,

but also with Titian, we find ourselves in nocturnal settings, mysterious, thanks to the warmth conjured by the wood, the

lit torches, ghostlike characters. Titian and Tintoretto are my favorites.

I also find very interesting the attempt, which unfortunately dates back to the Fascist period in Italy, of an architecture

that works well with not only painting and sculpture, but also the furniture of the period: a very beautiful example is also in Padua,

the Palazzo del Liviano, by the architect Gio Ponti, with frescoes by Massimo Campigli and sculptures by Arturo Martini.

Mario Sironi also comes to mind, who was a magnificent painter from the same period. These artists tried to recover ancient

aesthetics – from the Byzantines, the Italian Primitives – in order to conceive an art in continuity with the past,

yet at the same time modern.

That said, mind you, I am not a conservative! Born to a modest family that wouldn’t make sense. I just think that you

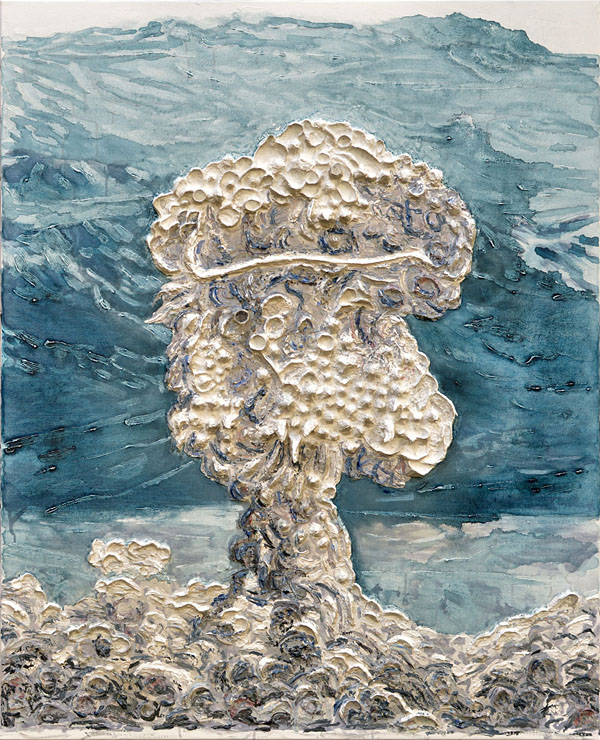

shouldn’t break from the past. And moreover, I think it’s impossible. My work Progetto Hiroshima clearly represents this.

For me, there isn’t inescapable progress, it’s a short-term thought. I believe that in art, like in other areas,

the past is knowledge that must be maintained, preciously guarded and kept like the wealth it is, in order to be able to build

the future on a solid foundation.

M.G. The fact that you pay a lot of attention to technique – I know you consult very old manuals – is this part of the same relationship you have with heritage from the past? I mean, not to aim for a sort of kitsch neoclassicism, but the will of a dynamic appropriation? The famous essay by the American critic Clement Greenberg, «Avant-garde and kitsch» comes to mind, written at the beginning of the Second World War, where he puts forth that avant-garde is the only true defense tradition has against the invasion of kitsch...

M.B. I have the impression that there are a lot of misunderstandings when speaking about «technique» or «tradition».

They are terms, which, like «decoration» or even «art», can have meanings that have become ambiguous today,

even pejorative. Mastering technique, for a painter, is a bit like knowing grammar for a writer. You need to be up to what you want

to express. I’m not convinced a tradition in painting still exists. Instead, I think there is a cultural and aesthetic heritage.

Different techniques, despite the manuals, is knowledge largely lost. In the atelier, an apprenticeship was carried out orally from

the master to the student, this practice was abandoned a long time ago and the state of preservation of works from the 1800’s

already shows the loss of knowledge in that period. Personally, I read manuals to understand how artists created such marvelous works,

but I’m aware that painting like artists from the past isn’t very useful, unless you want to have a career as a forger!

Moreover, there are techniques that I love for the material, such as frescoes and mosaics, however they are no longer possible today,

because you need to live with the times. I would add that drawing and painting appear long before writing, images that have reached

even us – I’m thinking of the Chauvet or Lascaux caves – despite their considerable age, are very familiar.

Perhaps humans are born with the ability to elaborate and perceive a certain spectrum of images? Perhaps tradition and technique

are condemned to evolve or to get lost over time, depriving numerous images of their cultural implications, but perhaps not of their

evocative power. I can’t decide.

Getting back to my painting and my relationship with technique and tradition, I can admit that I like that my paintings, even through

a contemporary tessitura, recall works from the past – Italian ones, why not? -, because of the colors or the composition.

It’s my cultural heritage. In fact, I think I’m fascinated by those who are able to make something new starting from an

old material. Lucien Freud, for example, painted nudes and portraits all his life, despite this he succeeded in creating new,

contemporary images, something that is extremely difficult to do. Moreover, you shouldn’t trust first impressions, a technique

can be seductive, but it hides a conceptual void. Painting a pattern on an enormous format, for example, can be impressive,

but it could be comparable to wearing a large, ostentatious watch on a wrist that is too thin. Every technical gesture must serve

the meaning of the work.

M.G. As you know, today we live in the era of digital reproduction of works of art, which leads to dematerializing them, standardizing an evanescent perception through bright screens. How do people react when they have direct contact with your paintings for the first time? How are your works perceived? What questions do people ask you most often?

M.B. People are often struck by the matter of the painting, which I would define as “generous”, but also for the wealth of colors.

They ask me what type of technique or painting I use.

I feel my paintings are rich in general, from both the chromatic and gestural

points of view. In fact, I am a music fan and I conceive painting like a musical composition; I hate monotony, flatness, mediocrity in art.

I prefer generous, passionate works. I imagine Soutine while he paints: his works breathe life, passion, his moods. You need to feel

empathy with the artist, imagine his life. In French (also in Italian), you say «birds of a feather flock together»...

This is also true for works of art. There are admired artists that I can’t stand when I think of them at work, because

I imagine how boring they are. For me, art must touch us at the most intimate level of our being, make us feel emotions.

M.G. What you are saying reminds me of the words of the English essayist Walter Pater, when he wrote in 1877 in an essay about Giorgione and the Venetian painters that «all art aspires to the condition of music». The formula is obviously applied very well to painting landscapes, but we can also think about non-figurative painting. Haven’t you ever been tempted by abstraction?

M.B. I have always been perplexed by the definitions «abstract» and «figurative». Given that the majority of

abstract painters who made this style famous were once figurative painters who had reached abstraction through a process of

synthesizing and re-elaborating reality. I feel abstract painting offers a non-narrative or non-representative vision, through

an unrecognizable interpretation of what is real. There is abstraction in figurative painting and figurative in abstract painting.

I’ve noticed that painting that becomes «abstract» often comes close to calligraphy or geometry, therefore, in some way,

to symbolic language or writing. This intrigues me, because in prehistoric caves, we already find «figurative» images

next to «abstract» signs. Even though I don’t know the scientific interpretation of these signs, I think they could be

ideograms derived from drawing. This means that at the same time the drawing could represent an image tied to the perception

of form and reality in the case of the animals drawn, and of a symbolic image tied to an idea, therefore to language, in the case

of the «abstract» signs. Consequently, our ancestors would have had an approach to drawing, which, deep down, wasn’t

so different to ours. And perhaps this is due to the same conformation of the brain, divided into a left and right side...

The least figurative cycle I’ve painted is the series of starry skies. The logic was to create a series of events within a

non-representative space. The result, like for numerous «abstract» artists, is a space of perception, a place of visual

emotion that maintains, despite everything, the grammar of classical painting with the search for perspective, etc. The sky as a

subject is interesting, because it’s completely imaginary, at the same time both figurative and «abstract».

Personally, I play a lot with this frontier between the representation of a precise image, above all when you look at the painting

in its whole, and an immersion into the matter, when you look at it up close.

M.G. You’re right: the binary opposition between figurative and abstract makes you forget the margins, the interstices, the visual ambiguities and this is a shame. But what you’re telling me also evokes the interest you have in Morandi’s painting, his repetition of very simple patterns, in rather austere natura morta, despite that enhanced by matter and lights that is both palpable and intangible at the same time...

M.B. Yes, Morandi in my opinion was an abstract painter. The subject, however, was there to suggest forms and compositions to him. Truth, in Morandi’s work, is effectively in the painting: if I think about his paintings, I visualize the subjects and I don’t find them interesting, but when I see them, I’m fascinated by the chromatic variations, the simplicity and elegance of the compositions. If we didn’t know anything about his personal life, we could think that Morandi was a monk who painted icons of strange divinities.

M.G. You work a lot in cycles. When do you feel that what you’ve been working on has come to an end, that there won’t be any new compositions for this theme? And what makes you start a new one?

M.B. I don’t have a recipe. At times my series are repeated for a long time, other times they are short-lived, and even, after years, I feel like picking them up again. I think a series finishes when I feel I have expressed what was important to me on the subject. Normally, the gestation period is relatively long, for example, for the last series, Die Natur, I had painted about ten small canvases in 2009, then I put them aside and didn’t show them to anyone. I returned to the subject in 2012, with much bigger formats: the starting point was the same images, but with a new dimension and the introduction of humans. The cycle was mature in the end.

M.G. Could you tell me about your series of cedar forests painted during a stay in Lebanon?

M.B. The Lebanese gallery director Fadi Mogabgab created, in a mountain village called Ain Zhalta, a summer residence for artists in the gallery. Fadi likes to stay with his family in the house next to the residence and take care of his artists. Nearby, there is the entrance to the Chouf nature reserve, where you can admire the famous cedar trees of Lebanon. I got permission to stay right in the forest. We set up different-sized tents and tied them with ropes to the trees. So the paintings were installed among the trees for the time needed to finish them. There weren’t visitors around so I was really alone in the forest! Even if I had often painted trees before that, it was the first time I had ever worked in a forest, I usually take some pictures and then work in my studio. But in Lebanon it was really special! I had set up about ten canvases, an entire area of the forest became my studio. It was a rather serene and very calm place. The trees were magnificent; I must say that I look for and prefer the older one, because they are marked by the signs of time, the trunk and branches are twisted and break under the weight of the snow: the posture of the tree narrates the effort of its existence, the need to rise towards the light, to free itself from the soil to reach the sky. Trees are a wonderful symbol of life, the fight for survival, but also of spiritual elevation. Plus, with their thick branches, cedars have something that recalls the human body.

M.G. In this series, I get the impression of a church nave and colors that recall certain 14th and 15th century frescos in Italian chapels. As you talked about your origins at the beginning of our conversation, Scrovegni Chapel in Padua obviously comes to mind...

M.B. These religious places are built on the foundation of the symbolism that comes from nature: in fact, the church as a building is the symbolic representation of the world, with its foundation that represents the earth and its cardinal points, altars and pillars, which, like trees, rise toward the celestial vault populated by saints, all dominated by god. The place of worship replaces the. But originally, nature was the sacred place, therefore the association you’re making isn’t random... When I did the paintings of Dreden after the bombing, the ruins for me suggested the carcasses of cathedrals; it was like representing the destruction of sacred architecture.

M.G. Despite the painting technique used is very different from yours, due to the smooth matter that characterizes it, I find that the way you explain the forest cycle as a natural model of a cathedral, is very near to certain paintings by Caspar David Friedrich, and more generally, to all the Gothic revival of the Romantics.

M.B. I love Friedrich’s work very much, his painting is very complex. I like the idea of getting excited by nature,

knowing how to transmit these emotions, without pathos, naivety, redundancy, but with simplicity and correctness. Friedrich was brilliant.

Like my photography professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Venice, Angelo Schwartz, used to say, it’s easier to take

a beautiful picture of an exceptional event than to find one in routine. Fortunately, there are artists who succeed in amazing us

without using special effects.

I feel like I have been inspired by many artists, from both the past and contemporary ones. So, even without wanting to,

this comes across in my paintings. I think that today western artists are orphans of a tradition rooted in what is sacred,

they still have the possibility of finding inspiration in history. In my opinion, this isn’t something to avoid or fear,

because for as much as you do or say, we’re products of history.

M.G. What are your current projects? Do you have a series that you’re thinking about or are you already working on something new that I haven’t seen yet?

M.B. At the moment I’m experimenting with new themes, but I can’t talk about it, because I’m not sure if

I want to show them. Instead, I can tell you that I’m continuing with the series Die Natur, in other words I’m looking for

a new way of expressing the relationship between humans and nature, whether it’s harmonious or conflictual.

Substantially, I think that artists put us before representations and in this way describe their world, which is often ours too.

Perhaps it’s banal to say it, but it’s important to keep in mind, because in reality nobody is obliged to adhere to an

artist’s vision. As far as I’m concerned, I offer representations of human society and what seems obvious to me,

in a world where a myriad of fields of knowledge can be easily accessed, it’s no longer possible to ignore «the others».

And when I say «the others», I don’t mean only our neighbors or colleagues, but also the air we breathe,

the water we drink, natural resources, etc. I feel an urgent need to conceive of a less selfish society, more attentive to

the world around us. My painting speaks about this, it gives a broader vision of the visible world and evokes the conflicts

that accompany human existence.

M.G. Rightly so, among your latest works is this large collective mural in Seine-Saint-Denis that features the Mother Goddess, who evokes the birth of civilizations. You can see children, adolescents and younger, in the photos of the work: how did you involve the neighborhood community in this collective work, did you give them precise instructions?

M.B. The title of this work is SOSPESA ("SUSPENDED"). The theme is the birth of civilizations. This suspended woman represents the Earth,

she is pregnant, at the same time evoking an archaic mother goddess, symbol of fertility, and a dead one. Therefore life and death,

the cycle of life. She is lying under a starry sky and you can see a constellation of colors that drips toward her from the wall

she stands out from. It's an archetypal image that can be found in many societies and civilizations since the origin of humanity

and it is this "universal" aspect that particularly caught my attention.

I was accompanied by a group of fifty-five people, both adults and children who worked freely, about ten of them are also

my students in Plastic Arts courses.

The participants had the task to create an image that represented a culture or civilization. I must specify that this work is in

the Les bosquets neighborhood (where the 2005 revolts took place, now undergoing complete reconstruction) and is located in front of

the “Tour Utrillo” (Villa Medici project of the 93rd department). Therefore, this work is also symbolic:

urban rebirth cannot take place without art and culture. My proposal, accepted by the Quai Branly Museum and integrated in

the program of the Ateliers Nomades, aims to move past ideological or religious fractures. The intention was to find a

common denominator for different cultures and, from this foundation, propose a collective work. Therefore,

I chose to give up total control in creating the work and sharing, in this way, its creation with the inhabitants of the area,

who at the same time will benefit from it.